I’ve rehearsed this moment many times over the years. I’ve thought about it, planned for it, even written it down. You tend to think about this moment a lot when your father has almost died as many times as mine has. You think about it when you’re sitting folded over at the waist in plastic emergency room chairs at 4 in the morning as many times as my mom and I have, staring at monitors or looking for the rise and fall of his chest to ensure he’s still there.

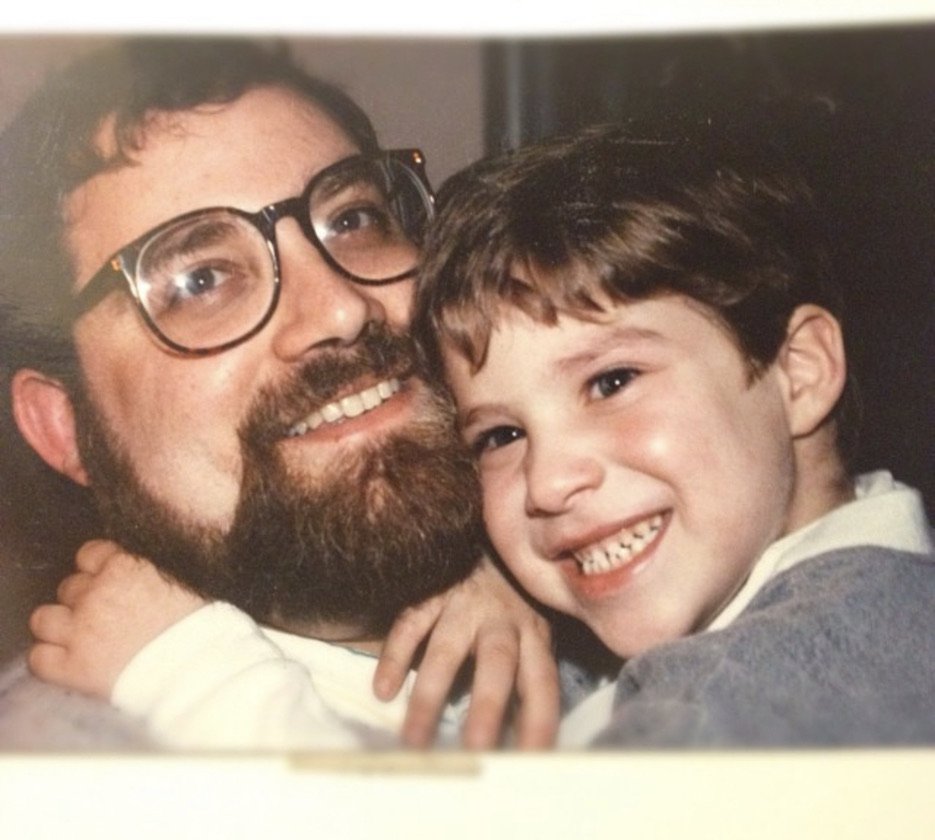

These things give you enough time to think about how to tell the story of a man you barely had a chance to know before his life went from authoritative father to the version of what happens to a person when their brain starts to kill them from the inside out. And every time I’ve thought about this moment, I’ve always known I would start and end with a terrible joke.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

There were two elephants sitting in a bath tub and one turns to the other and says "Pass the soap" and then the other one says, "No soap, radio.”

I hate this joke. I’ve hated it my whole life. My dad loved this joke, the way he loved many terrible jokes. He loved telling this joke, laughing without fail, every time he got to the end. He would tell it to friends, family, customers who were just trying to buy a cordless phone battery. Me. He would tell this joke all the time because he loved it. It was his favorite joke.

I hated “No soap, radio.” I didn’t get it. I couldn’t understand why he loved it so much, and I resented the joke for being this supposedly funny thing that I couldn’t understand. And in some ways, this juxtaposition - this inability to see eye-to-eye about even the simplest things - pretty much defined our dynamic until his Parkinson’s disease started to get really bad.

I was just leaving high school when he was first diagnosed. I was a teenager. He was just turning 50, which is nine years older than I am right now. He first started showing signs of his disease around 48, which is seven years older than I am right now. At the time, he was considered young for the disease, but it wasn’t unheard of. Michael J. Fox (the extraordinary face of most people’s perception of Parkinson’s), was diagnosed at 29, and eventually told the world about it at 36. A quarter century ago, Parkinson’s was still mostly known as an old man’s affliction, coming on aggressively and late in years. Being diagnosed at fifty was a blessing and a curse. It was early enough to be at the cutting edge of scientific research and remedy, with a long enough amount of life left for that research to surpass what it could do to still help a man at an advanced age and stage of neurological loss. He’d been sick more of my life than not. He’d been sick more of my life than he was of his own.

In the mid-2000s, when my father’s symptoms were starting to really impact his quality of life, he underwent surgery to have a device implanted into his brain that would, at least for a time, get his tremors under control and help with very basic cognitive issues. On the eve of that surgery, he wrote me a letter as a kind of ethical will, and gave it to me early the next morning in case he never made it through. It was brain surgery, after all. In the letter, he reflected on the life the three of us had lived, and shared his hopes and dreams for what my life would one day bring. He also shared his fears and concerns for his well-being, and how much he worried he’d never live to see me accomplish those things he and my mother dreamt for me.

And on so many of those 4AMs, when we never knew if we’d all be leaving the hospital together or if my mother and I would be embarking on a new journey the way we are now, I would think of this moment and the complexity of grieving the loss of someone we’d lost and grieved already at so many difficult and complicated times. How do you let go of someone who’d been taken from you over and over again? I’d think of the daunting task of eulogizing a man who had such character and dominance in my head - an incredibly stern father, a proud Jew, a man of ethics and liberalism, pious in education and rabbinic in so many settings, a hard worker, a well-regarded businessman - and I considered that perhaps, when the time came, I’d read his letter to all of you. In the countless moments I’ve re-read it over the years, and the several times I’ve re-read it over the last week, it’s always felt like a perfect reflection of him, even in the parts where he calls me his legacy. Even at the end, when he wrote that through me, he goes on living.

But instead, I want to share a different piece, something I found over this insanely horrible last week, something I wrote 13 years ago. In fact, it was something I wrote 13 years ago today, July 28, 2011.

When they gave us the news last week that we were reaching the end - that an IF we’d all wondered about for years had now become a WHEN - I went looking for these long archived pieces of writing and found myself struck by the gift that past Ari had prepared for me in this moment, where I’d preserved key details of what life was like for all of us back then. And amongst them, I found the following, which I’d written when my parents were both 60, and I was 28, and we all still lived together at home, instead of in three different places, and now, two.

Some days are better than others. Same with the nights. Tonight is a good night.

When I was a boy, my dad and I went through a process together just so I could go to sleep. He would put me to bed with the following mantra, kissing me on the top of the head as a break in between each phrase:

Have a good night sleep, pleasant dreams, and wake up happy and well tomorrow morning. Sweet dreams. I love you.

This happened every night.

Eventually I aged out of the process and it just sort of stopped. I don't think it happened on a specific night...it just became one of those things, like crossing the street without holding hands, that we eventually own for ourselves with age. At some point, I started going to sleep without his bedtime mantra.

In the past few years, my dad has had difficulty getting to sleep. The Parkinson's makes it hard for him to coordinate his upper and lower muscle groups to allow him to swiftly or effectively climb into bed. This is a prime example of very basic movements that we take for granted. My dad undergoes this awkwardly choreographed process of sitting down, shifting weight to his arms and wrists, pushing his feet against the side of his bed and pivoting into a supine position that sounds quite normal but can take a lot of time and effort.

Some times he has to do this while trying not to wake my already-sleeping mother. Other times, like in the middle of the night if he needs to get up for any reason, he must do it in the dark. Needless to say, it's not an easy component to his daily routine and it puts a lot of unnecessary stress on his body and mind right before bed time, when science dictates that you should be avoiding stress altogether.

As a result, especially in the past few months, there are many nights where my mother and I help my father into bed. Considering that the Parkinson's can also render him as dead weight, it can be very difficult just getting his legs or his torso positioned in a way where he'll feel safe from accidentally falling out of bed.

As rough as this whole thing is, it's hard not to think that I'm getting incredible practice for my own children someday. Based on my adventures in babysitting, an unruly child who wants a drink or another bed time story is cake compared to this process.

Now that we have revisited bed time, however, my father has often taken the chance to bend his neck, kiss my head and repeat that mantra from my childhood. What would most likely feel cloying or ill-advised at my age has once again become the best part of my day.

Tonight, on his way to bed, I asked him if he thought he'd need help and I stood at the ready in case he did. With what appeared to be no effort whatsoever, he gracefully pulled off this strange getting-in-bed dance in mere seconds, pivoting into position and laying down comfortably in nearly one full movement. It was a stark reminder of how unpredictable Parkinson's can be...for weeks he'll have difficulties and then on one seemingly random night, he's got it all on his own.

No matter. It's amazingly reassuring to watch him effortlessly do things that we take for granted, especially when they're usually so taxing on him. It's a fantastic sign that even on his darkest of days, he's still in there, still my dad.

Goodnight, Abba. Have a good night sleep, pleasant dreams, and wake up happy and well tomorrow morning. Sweet dreams. I love you.

Harry Halbkram - Asher Moshe ben Laibel Reuven - was proud to be from the city of William Penn and Rocky Balboa. When I was little, he’d take me to Phillies games and spend the whole time filling out the box score with a little pencil and anxiously trying to protect my tiny ears from the drunken tirades and unpredictable raucousness of his fellow Philadelphians. He loved a cold beer and a kosher hot dog and a soft pretzel with a thick bead of spicy mustard. He loved Star Trek, and Field of Dreams, and jazz. He took extra long showers, and would type on a keyboard by hunting and pecking for the keys with just his pointer fingers, and he loved having his back scratched, especially up between his shoulder blades. He loved his Judaism and took great pride in the storied tradition of being its student, teacher, and practitioner. He’d be the first to appreciate that we took effort to make this service as respectful of, and as committed to, the law as possible, even if he would have hated the reason for it. He would been tickled that my eulogy was typed and printed double-spaced, just as he taught me my bar mitzvah speech should be. And he would have been moved that I ripped apart the collar of my shirt on Thursday morning after he was gone. He loved my mom, and loved me, too, even when he had the strangest ways of showing it. On Friday nights when it was time to make Shabbos, he would extol my mom as his aishes chayel, his woman of valor, even if he never recited the literal proverb from where the phrase originates. And he would clasp his hands above my head and recite the birkat kohanim, the priestly blessing, wishing for me peace, grace, and eternal protection, which he did just the same as a young adult as he had when my head was tiny enough to fit inside his palms. And he loved a terrible joke. He would relish the chance to tell a terrible joke whenever he could. He would tell them to friends, family, customers who were just trying to buy a cordless phone battery. Me.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

Two antennas met on a roof, fell in love, and got married. The ceremony wasn’t much, but the reception was incredible.